Colombia’s new government eyes Venezuelan gas

Colombia’s new government is racing to wind down the oil and gas industry but also signalling that it could resort to neighbouring Venezuela to replenish gas supply.

Colombia’s new government, intent on accelerating an energy transition, is racing to wind down the oil and gas industry but also signalling that it could resort to neighbouring Venezuela to replenish gas supply once the country’s own reserves are exhausted.

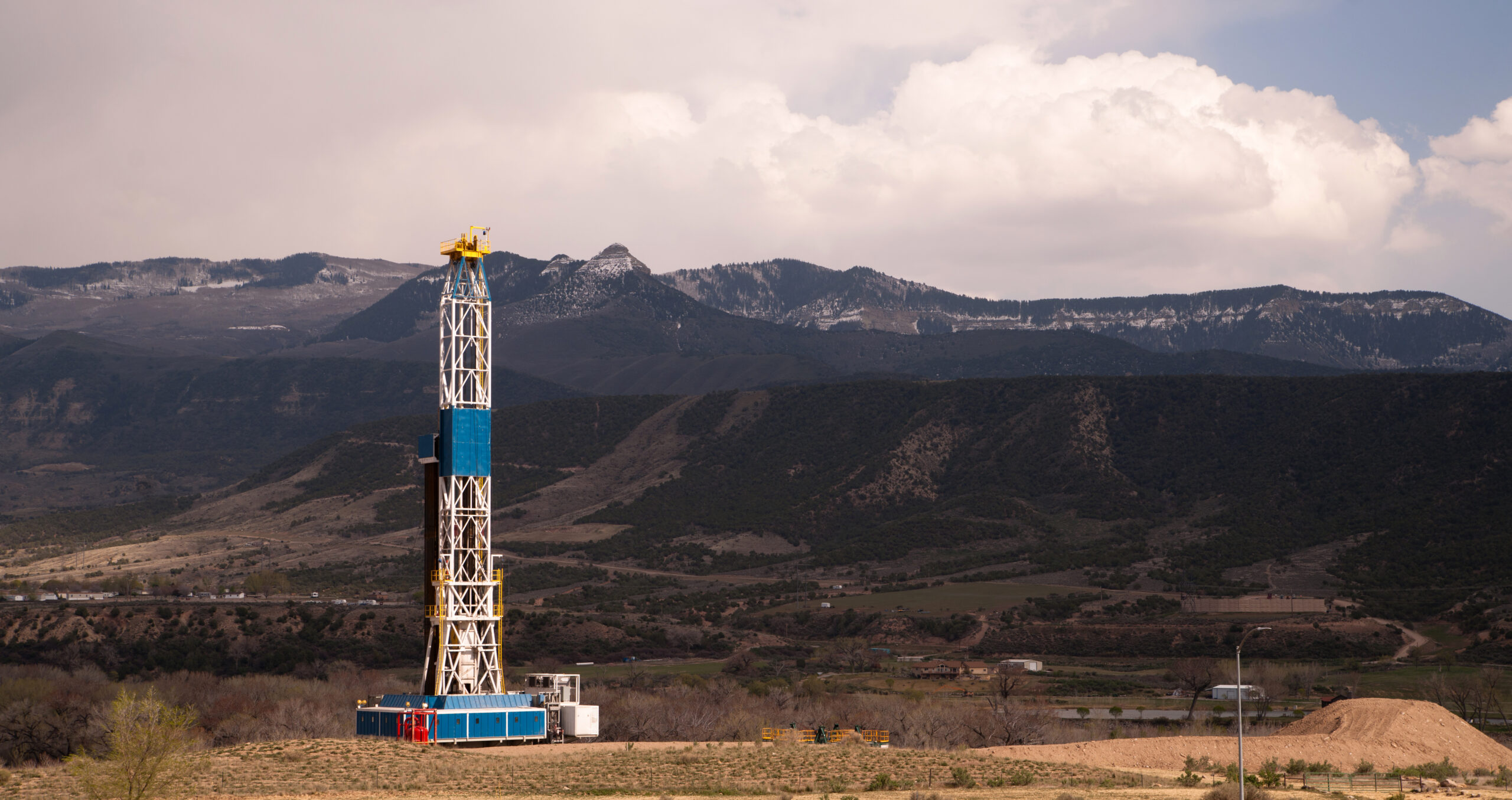

Gustavo Petro, a leftist former guerrilla who was sworn into office on August 7, wants to ban unconventional oil and gas drilling and all new conventional exploration. His policy prescriptions, which speed up a transition path rolled out by his conservative predecessor Ivan Duque, broadly align with global efforts to phase out fossil fuels that are the main driver of life-threatening climate change. But critics say Petro’s lightning strategy would expose Colombians to supply risks and price spikes, particularly in the gas sector.

“After using up the gas reserves that we’re told will last seven or eight years, if we still need to supply our energy system, this could be done with the gas transport connection with Venezuela,” new mines and energy minister Irene Vélez said at a high-profile Colombian business conference in Cartagena on August 12.

Her remarks triggered a sharp reaction, even from within the governing coalition’s own ranks.

“Energy transition is a vital obligation but TRANSITIONS ARE TRANSITIONS! Gas cannot be replaced from one day to the next,” Senate president Roy Barreras, a Petro ally, said on Twitter in response to the minister’s remarks.

“The gas we consume is produced 100% in Colombia. Today we haven’t been affected even by the price impact that the European Union has seen as a result of the war between Russia and Ukraine, and we should maintain this self-sufficiency to distance ourselves from these price fluctuations,” said Luz Stella Murgas, president of the Colombian trade group Naturgas.

Buying time

Colombia and Venezuela already share a cross-border gas pipeline, but it has long been inoperative in spite of Venezuela’s abundant reserves and Colombia’s looming supply deficit. Petro’s decision to restore diplomatic relations with Caracas, which were severed by the Duque administration in 2019 as part of an international campaign to isolate Venezuela’s autocratic regime, is now reviving hope of gas trade. If it can be pulled off, Venezuelan supply could potentially buy time for Colombia to build up its renewable energy base.

The challenges are daunting. Even though Venezuela hosts some of the world’s largest oil and gas deposits, production led by national oil company PDVSA has collapsed over the past decade because of mismanagement and a lack of investment. This downward trend was exacerbated by US financial sanctions on Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro’s government in 2017 and oil sanctions in 2019. In spite of some tweaks, the sanctions remain in place, and so has Maduro.

Venezuelan offshore gas, produced by the Cardon IV joint venture between Spain’s Repsol and Italy’s ENI at the giant Perla field, is an exception to Venezuela’s hydrocarbons collapse. The field has been under-producing for years, because PDVSA, the sole offtaker, struggles to pay for the supply, and has limited capacity to absorb it.

Under Venezuelan law, PDVSA is the only company permitted to export, and few in Colombia believe that the company would be a reliable counterparty. The domestic pipelines in Venezuela needed to move the gas onshore and across into Colombia are in bad shape as well, and owner PDVSA does not have the money to repair them.

“Cardon IV is a key actor here, because it is the main source of supply in western Venezuela. The main challenge is infrastructure,” Antero Alvarado, managing director of consultancy Gasenergy Latin America, told Gas Outlook.

He cites as an example the Ulé-Amuay pipeline system that runs between PDVSA’s Amuay onshore refining terminal and a western distribution hub that connects with the Antonio Ricaurte cross-border line.

Historic tensions

Even if the infrastructure could be repaired, Colombians are wary of relying on Venezuela for vital gas supply in light of historic tensions. They look to Russia’s growing curtailment of gas supply to Europe, and Argentina’s cutoff of supply to Chile in the mid-2000s, as evidence of the risks to energy security before Colombia fully transitions away from fossil fuels.

Another gas discovery off Colombia’s Caribbean coast underscores the potential for the country to tap its own resources to complement onshore production of around 28 million cubic meters a day, and LNG imports that supply three thermal power stations.

Shell, partnered with Colombia’s state-controlled oil company Ecopetrol, has confirmed the presence of gas at the deepwater Gorgon-2 well on the Col-5 block. The well result was announced on August 10, just three days after Petro’s inauguration. His administration has said that existing exploration contracts would be respected.

A new southern Caribbean gas province “could significantly contribute to supporting the country’s energy security and opens the possibility of future gas exports, a fundamental energy source for the energy transition that Ecopetrol has been developing,” Ecopetrol said.

Operator Shell and Ecopetrol are 50:50 partners in two other offshore blocks, Fuerte Sur, and Purple Angel. Other foreign companies with a presence in Colombia’s Caribbean offshore province are Repsol and US firms Occidental and ExxonMobil.