U.S. LNG building boom threatens climate goals

Two dozen LNG projects are in the works in the U.S., but the rush for gas is both a financial and a climate risk, according to two new reports.

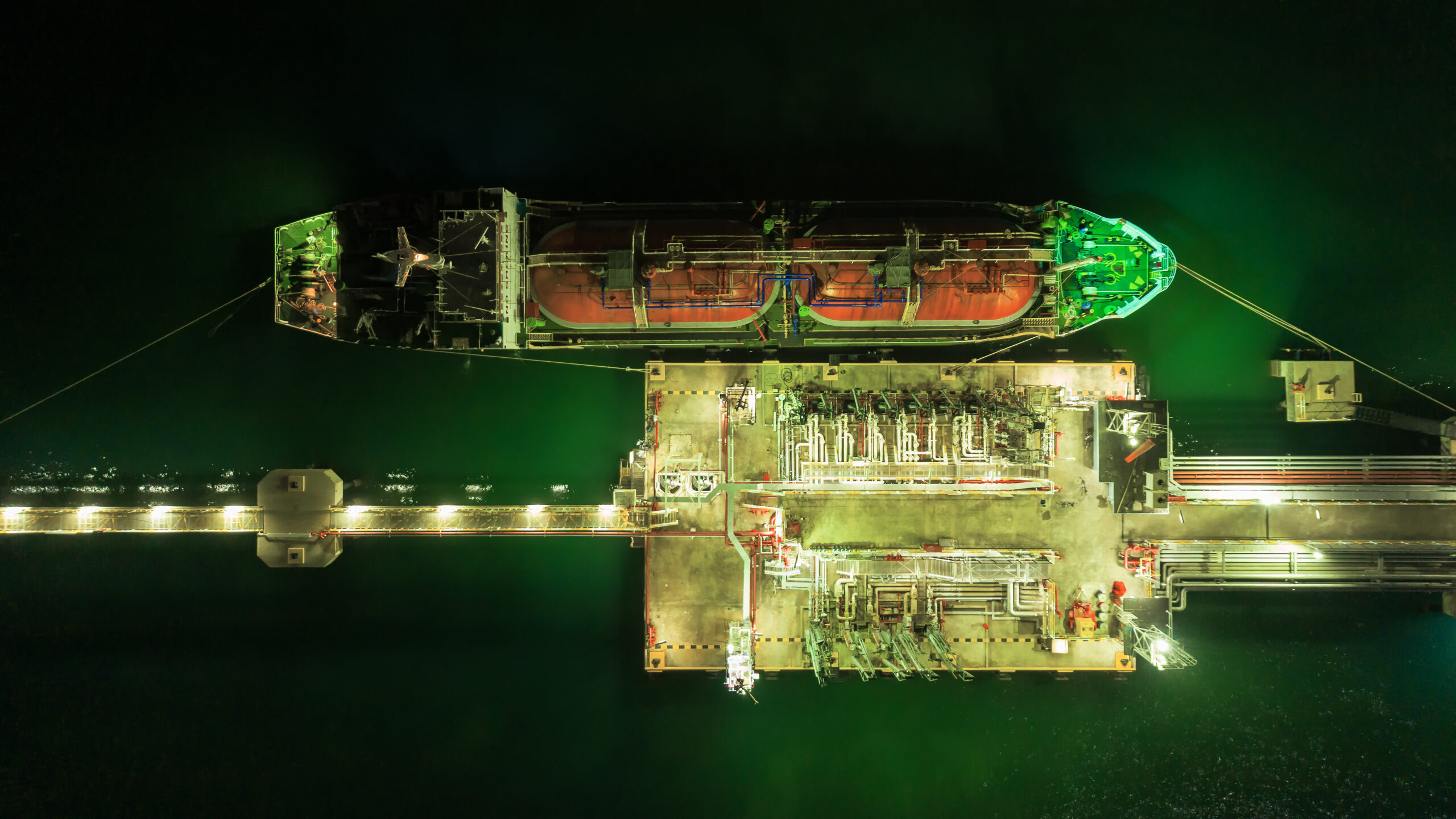

The spike in global energy prices, and the European Union’s attempt to find alternative sources of Russian gas, has set off a flood of interest in new liquefied natural gas (LNG) supply, and a spate of deals inked along the U.S. Gulf Coast could pave the way for a new building boom. But the scramble to build new LNG terminals heightens the risk of leaving more assets stranded while also threatening climate disaster, according to two new reports.

The U.S. currently has seven operating LNG terminals, and four brand new facilities are under construction in Texas and Louisiana. Another nine have permits in hand, but have not yet begun construction. A further 12 projects are seeking federal authorization.

The estimated 25 LNG projects in the U.S., most of which have not yet broken ground, could result in annual greenhouse gas emissions in excess of 90 million tons per year, equivalent to adding 20 new coal-fired power plants, according to a new report from Environmental Integrity Project, a Washington D.C.-based nonprofit.

That estimate vastly understates the real impact since it only accounts for emissions from the facilities themselves, excluding the methane released from fracking, pipelines, and also leaving out emissions when consumers burn the gas overseas.

“Although there is pressure to hurry up approvals of these LNG projects, government regulators should be careful and thoughtful in considering their significant environmental impacts,” said Alexandra Shaykevich, Research Manager at the Environmental Integrity Project (EIP). “A dramatic increase in global dependence on LNG could be risky, from a climate perspective.”

A separate report comes to a similar conclusion, finding that LNG expansion in the U.S. is “inconsistent” with climate goals.

“The climate pathways compliant with limiting average global warming to 1.5°C don’t match the current push to expand LNG production and utilization,” Shruti Shukla, an international energy advocate at the Washington-based Natural Resources Defense Council, and a co-author of the report, told Gas Outlook.

The U.S. is already off track to meet its 50 to 52 percent greenhouse gas emissions reduction goal by 2030, and locking in the emissions from an expanded gas and LNG export industry would push those targets further out of reach.

The gas industry advertises fossil gas as a cleaner alternative to coal, but that logic ignores the fact that methane leaks at all stages of the supply chain. With a warming potential more than 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide, leaking methane from gas infrastructure wipes out any perceived benefit over coal.

“Clever marketing can only take the LNG industry so far,” Shukla said, referring to the gas industry’s claims. “The world has embarked on a long-term plan to decarbonize its energy systems. Expansion of unabated gas production is not a helpful strategy from the LNG industry.”

Building now, stranded later

Another pitfall to building a bunch of new LNG terminals is that their time horizons don’t match up with climate targets or the pace of energy transition. New LNG terminals will take years to build, making their relevance to today’s energy crisis questionable.

“This is nothing but fossil fuel industry profiteering and exploiting the tragedy of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a pretext to chase profits all over the world,” Zorka Milin, a senior legal adviser at Global Witness, told Gas Outlook. She pointed to the report from Environmental Integrity Project, which showed that many of the buyers for new LNG supply from the U.S. Gulf Coast are in Asia, not Europe, where the gas is supposedly needed.

“Truth is, this gas rush won’t do a whole lot to help America’s European allies – but will certainly help to enrich American fracking executives,” Milin said.

Moreover, once online, LNG terminals are intended to operate for several decades. Anything built in the mid-2020s could theoretically be still operating in the second half of this century, well beyond the time when the world is supposed to be hitting net-zero emissions targets.

“This means that building these new projects will doom our collective global climate goals if these terminals continue to operate during their entire expected lifespan,” Milin said. “Otherwise, if they are decommissioned, then their investors will be stuck with stranded assets. So, it’s a lose-lose proposition.”

Even if the new LNG supply were a solution to the current crisis, the demand is temporary. For example, the EU is aiming to slash greenhouse gas emissions by 55 percent by 2030, including a reduction in gas demand. But LNG infrastructure is expected to operate for decades.

“Within this context any new U.S. LNG project that comes online mid-decade could end up in a global market with lower prices and a potential supply glut,” Shukla said. “With ratcheting federal and states- led actions for reaching net-zero targets in the coming years, there is a strong risk that any new carbon intensive infrastructure could easily become stranded assets.”

The current rush for new gas is a risk financially, and a threat to the climate. “Everyone benefits from switching to non-fossil options under their energy transition plans instead of taking the dirtier and expensive roundabout way to reaching respective net-zero targets mid-century,” Shukla said.