COP28: flurry of climate pledges, but phaseout showdown looms

In the first week of COP28, the U.S. and Canada announced or joined a long list of climate initiatives. But both countries, along with other major producers, are reluctant to commit to the larger task of phasing out fossil fuels.

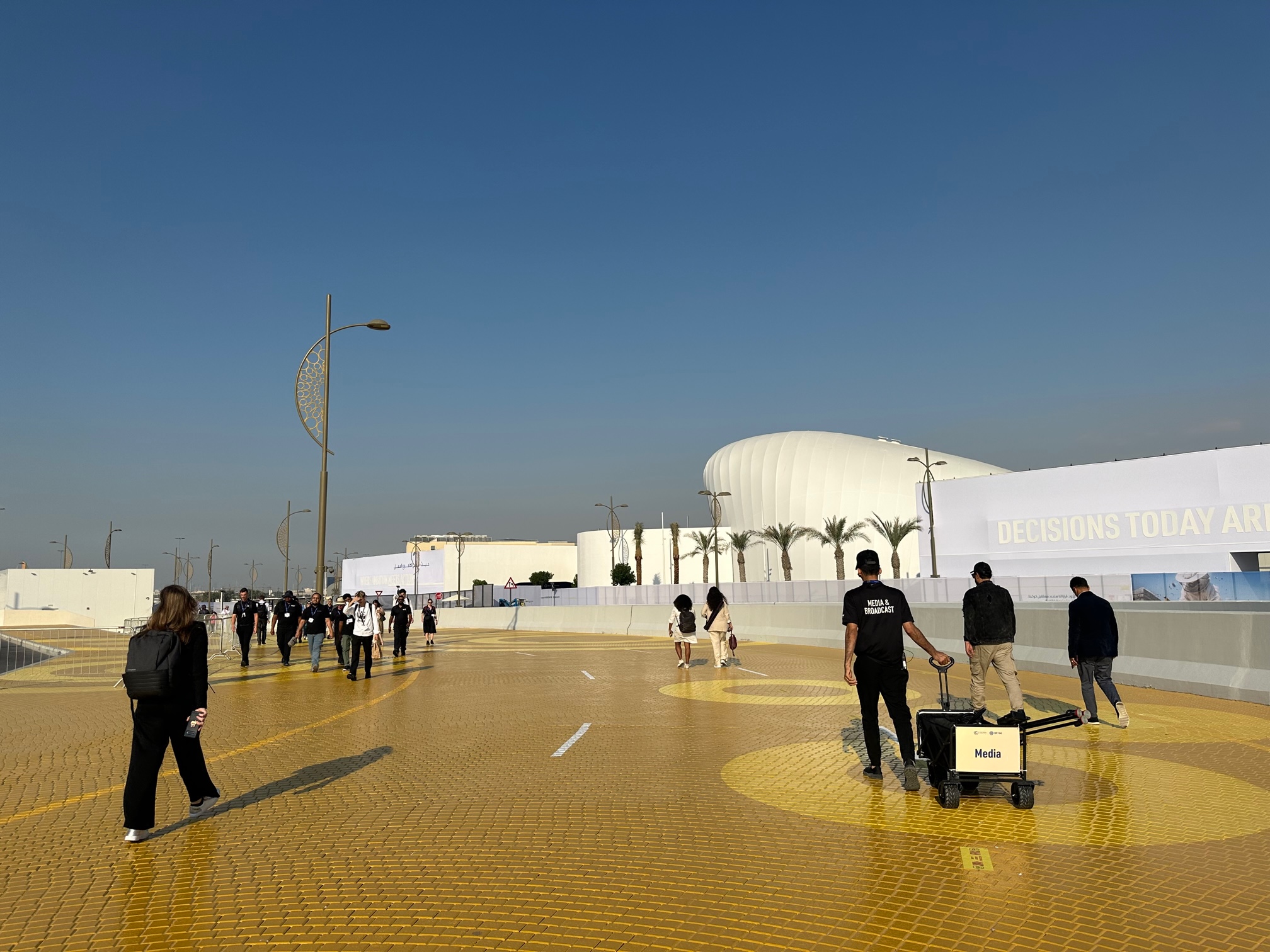

At the COP28 summit in Dubai, the U.S. and Canada have announced significant steps to cut climate pollution from their energy sectors, while simultaneously avoiding meaningful constraints on production growth.

As thousands of delegates gathered in Dubai, the planet’s vital signs continued to worsen. 2023 is now officially the hottest year on record, and November was 1.75 degrees warmer than the pre-Industrial Age average. New research shows that the global warming has already advanced to such a degree that the world is at risk of breaching five “tipping points” that will bring about potentially irreversible catastrophic climate change.

While all COPs are important, notwithstanding the forum’s flaws, the current proceedings come at a pivotal point. Some analysts see global greenhouse gas emissions potentially reaching a peak in the very near future, but steep and aggressive cuts are not yet in the offing. Urgent action is needed to slash greenhouse gas emissions.

At the summit, there were some notable steps forward. At an event hosted by the U.S., China, and the UAE, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency unveiled highly-anticipated regulations on methane emissions from the oil and gas industry, which is the largest source of methane emissions in the country, accounting for roughly 30 percent of the total.

The regulations will not only apply to future wells drilled, but also to existing oil and gas infrastructure. The new rules will cut methane emissions by 80 percent by 2038, relative to a business-as-usual scenario, according to the EPA.

The rules would require oil and gas companies to invest and implement equipment that does not leak methane. It would phase out routine flaring and requires sites to be monitored for leaks. In light of the government’s inability to closely watch every piece of infrastructure, the rules allow for third parties, such as watchdog groups, to have a role in reporting on “super emitters,” or large sources of methane pollution.

Environmental groups hailed the new rules. “EPA’s limits on oil and gas methane pollution are a vital win for the climate and public health, dramatically reducing warming pollution and providing vital clean air protections to millions of Americans,” Fred Krupp, president of the Washington-based environmental group EDF, said in a statement.

Canada also announced methane rules on oil and gas, with the aim of cutting methane emissions by 75 percent by 2030, from a 2012 baseline. Canada’s large oil and gas sector is also a huge source of methane pollution — and may be far worse than official data suggests. A recent study estimates that methane emissions from the oil and gas sector in Alberta are underestimated by 50 percent.

“At a COP so focused on closing the implementation gap, it’s important to see Canada move from promise to regulation on methane emissions,” said Caroline Brouillette, Executive Director, Climate Action Network Canada. “Now to finally tackle the oil and gas industry’s growing pollution, Canada’s framework to cap oil and gas emissions must be published as soon as possible with a science-aligned target.”

The Canadian government is soon expected to unveil its cap on emissions from the oil and gas sector.

While cutting methane pollution was the most substantial announcement, both the U.S. and Canada launched or joined a flurry of other initiatives.

The U.S. and Canada were among 63 countries that joined a pledge to cut cooling-related emissions, a segment of greenhouse gas emissions that would otherwise likely increase in the years ahead as the planet warms and even regions with temperate climates increasingly adopt air conditioning. The pledge calls for at least a 68 percent cut in cooling-related emissions by 2050 from 2022 levels — a daunting challenge given that cooling capacity is expected to triple by mid-century, as Reuters reports.

In another popular initiative that has received global support, the U.S., the EU, and the UAE led a group of 118 countries in a call to triple renewable energy capacity by 2030.

The Biden administration also supports a phaseout of coal power plants, along with 56 other countries.

The U.S. said that it would work with 30 other countries to advance nuclear fusion, a potentially game-changing clean energy technology, but one that remains far away from commercialization.

Through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the Biden administration joined the Green Guarantee Company, a public-private partnership aimed at offering green bonds to lower-income countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

The Biden administration said it would give $3 billion to the Green Climate Fund, which provides money for climate projects in developing countries. While that announcement made headlines, it comes with a rather large caveat — the money needs to be approved by Congress, which may be difficult in the Republican-controlled House of Representatives.

COP28 fossil fuel phaseout?

A series of important, but relatively small-bore climate initiatives are certainly welcomed, but are not enough to really move the needle on global greenhouse gas emissions, at least at the speed required to address the climate crisis. The elephant in the room, and the looming challenge that awaits the Dubai summit, is whether or not the world will declare a need to “phaseout” fossil fuels.

Quibbling over the semantics will continue in Dubai, but current tends illustrate why the agenda item is so important. U.S. oil and gas production is at record levels and will continue to rise, which will offset some of the climate gains accrued from a variety of rules and regulations. Even looking narrowly at methane, stricter limits on methane pollution may be overshadowed by more leaks from the proliferation of new oil and gas wells and associated infrastructure.

Meanwhile, a highly-publicized oil industry-led initiative announced at COP28 by the world’s largest energy companies, called the Oil and Gas Decarbonization Charter, pledges to cut methane emissions to near-zero by 2030 and to also achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. But the initiative is all voluntary, and excludes Scope 3 emissions, which accounts for 80 to 95 percent of the emissions of the oil and gas industry.

“The COP28 Presidency-led Oil and Gas Decarbonization Charter is a lot of fanfare around the restatement of woefully insufficient emissions reductions pledges already made by many of the signatory corporations,” said Kathy Mulvey, accountability campaign director at the Washington-based NGO Union of Concerned Scientists.

That stands in sharp contrast to the refusal by any major energy-producing nation to endorse a call to limit fossil fuel production. According to Reuters, 69 of the world’s oil producing countries, including the United States, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, have committed to net-zero emissions, but only three tiny energy producers — Denmark, Spain, and France — have actually announced plans to stop drilling.

“Less than a week into negotiations, we have serious concerns about fossil fuel industry influence—both public deception and behind-the- scenes manipulation—and the risk it poses to securing the scientifically-necessary agreement for a fast, fair, and funded phase out of fossil fuels at COP28,” Mulvey said.

The Dubai talks have been pilloried for the enormous presence of oil and gas lobbyists. But despite the industry influence, the language calling for a “phaseout” of fossil fuels is still alive, and appears in one of the draft texts being circulated in Dubai.

On December 6, the prospects for a phaseout received a boost, when U.S. climate envoy John Kerry said that the U.S. supports a phaseout of fossil fuels.

“If you’re going to reduce the emissions, and you’re going to actually hit the target of net zero by 2050, you have to do some phasing out,” Kerry told reporters. “There’s no other way to get to that target.”