Colombia braces for oil and gas phase-out decision

The oil and gas industry in Colombia is on tenterhooks as the government decides whether to allow new exploration contracts or not, as it moves away from fossil fuels.

BOGOTA, COLOMBIA — The oil and gas industry is bracing for a government decision on whether to allow new exploration contracts as it transitions away from fossil fuels, a process that Bogotá is seeking to harness to make deep social and economic changes.

President Gustavo Petro, a former guerrilla turned leftist politician, took office in August with a pledge to accelerate Colombia’s energy transition by shutting down awards of new exploration contracts. While Petro has long held this position, his administration has conveyed mixed signals to an industry that plays an outsized role in Colombia’s economy.

“We are fulfilling a campaign promise…Today, we are not going to sign new exploration and production contracts,” mines and energy minister Irene Vélez-Torres said in a recent radio interview, echoing earlier remarks by deputy energy minister Belizza Ruiz Mendoza.

Finance minister José Antonio Ocampo has struck a more measured tone, saying the government would respect existing contracts as it studied “how many (new) contracts would be needed, which will depend fundamentally on the exercise of a long-term program to see at what pace we can diversify our exports.”

The oil and gas industry in Colombia is on tenterhooks. “The government is doing an analysis of current contracts to see whether the country needs new contracts and then it will take a decision. An answer is needed very quickly, because this is causing some uncertainty and that’s not good,” Ismael Arenas, president of the Colombian Association of Engineers (Aciem), told Gas Outlook on the eve of a major industry conference in the Colombian capital of Bogotá.

In a closely watched speech at the opening of the conference on November 16, Velez-Torres said the government will try to reactivate 35 upstream contracts that are currently suspended for various reasons, such as security risks or permitting snags, in order to eke out more supply from existing agreements. Among the companies holding such contracts are Canadian independents Gran Tierra and Parex, Gas Outlook has learned.

The minister, a former environmental activist, rushed out of the conference venue without responding to reporters’ questions about new exploration.

In her presentation, Velez-Torres outlined the pillars of the administration’s new six-month process of developing a “just” energy transition roadmap. “We have called this ‘just’ because we believe that the energy transition is not just about a transition of technologies, but it is also an opportunity for transformation of a social and economic model that in our country up to now has proved to be profoundly unjust, for which we have had more than six decades of armed conflict.”

Consulted on the sidelines of the event, oil and gas industry executives expressed caution as they await more policy definition. They say Colombia needs exploration and production to help to pay for the inevitable transition away from fossil fuels. That view is echoed by many economists, including Colombia’s former finance minister and Columbia University professor Mauricio Cárdenas.

As Petro and his team consider options, the industry and governments of oil-producing regions such as Meta in central Colombia that rely heavily on royalty revenue are pressing them to allow drill-bits to keep spinning. “We are convinced that exploratory activity is needed not only for the country’s energy security but also to continue exports to support the economy,” Arenas said.

Nelson Castañeda, president of oil contractors’ chamber Campetrol, expressed confidence that the government would allow new exploration in order to meet its budget needs. Between 2011 and 2021, the oil and gas sector accounted for 42% of Colombia’s exports and 23% of direct foreign investment. “If the oil industry does well, the country does well,” he said.

Colombia’s state-controlled Ecopetrol, by far the country’s biggest oil producer and exporter, has adopted a low profile as the new administration develops its transition policies. With former BP executive Felipe Bayon at Ecopetrol’s helm, the company has adopted detailed transition plans of its own, with a focus on renewable energy for its operations and low-carbon hydrogen pilot projects.

Executives warn that Colombia has previously endured a hiatus in exploration, with steep consequences for production and revenue. Between 2013 and 2018, there were no new exploration contracts. This led output to tumble from 1 million b/d in 2015 to about 758,000 b/d today.

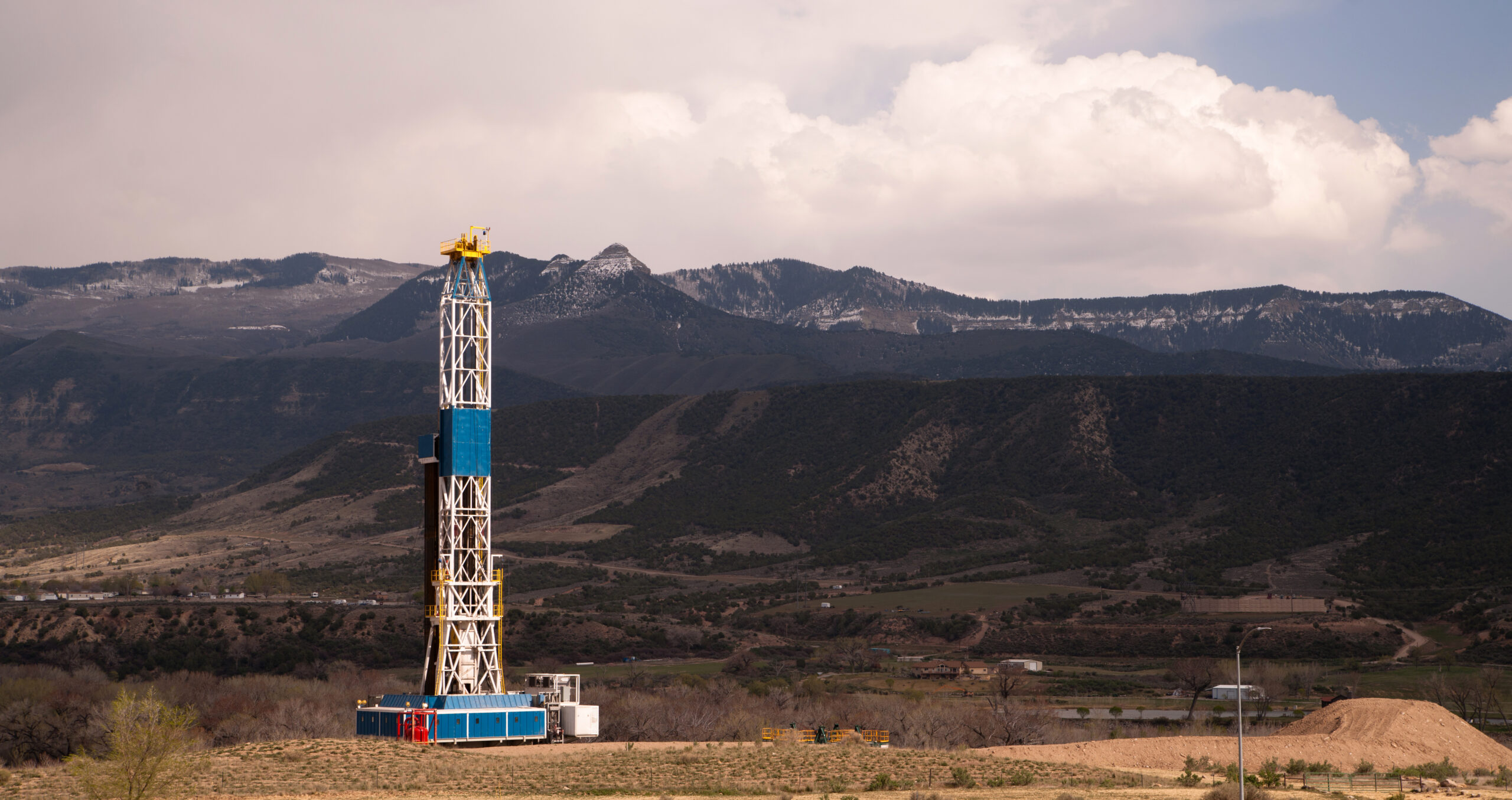

Even if exploration is allowed to proceed, there is no guarantee that Colombia will uncover significant new reserves in its mature onshore reservoirs. There have been no major new discoveries here for years, and the Petro administration put a stop to a plan for unconventional pilot projects using hydraulic fracturing, better known as fracking, that Ecopetrol had hoped to develop in partnership with ExxonMobil. Offshore Caribbean reservoirs are widely seen as a promising frontier to replenish Colombia’s reserves base.

At current production and price levels, Colombia currently has 7.6 years of oil reserves and eight years of gas reserves. Without new exploration, the reserves will run out long before the world weans itself off of fossil fuels, with implications for the Colombian people, the industry says. The impact would be especially evident in Ecopetrol, and the government coffers that depend on it.

“If Ecopetrol doesn’t replace its reserves through exploration, its reserves will fall, and the company’s value in the market will decline, and we will become even poorer,” said Luis Miguel Morelli, former head of Colombia’s National Hydrocarbons Agency (ANH) that oversees oil and gas contracts. “I hope the government reviews this decision … which would cause a lot of economic harm to the country.”