EU-Norway Green Alliance: hype or hope?

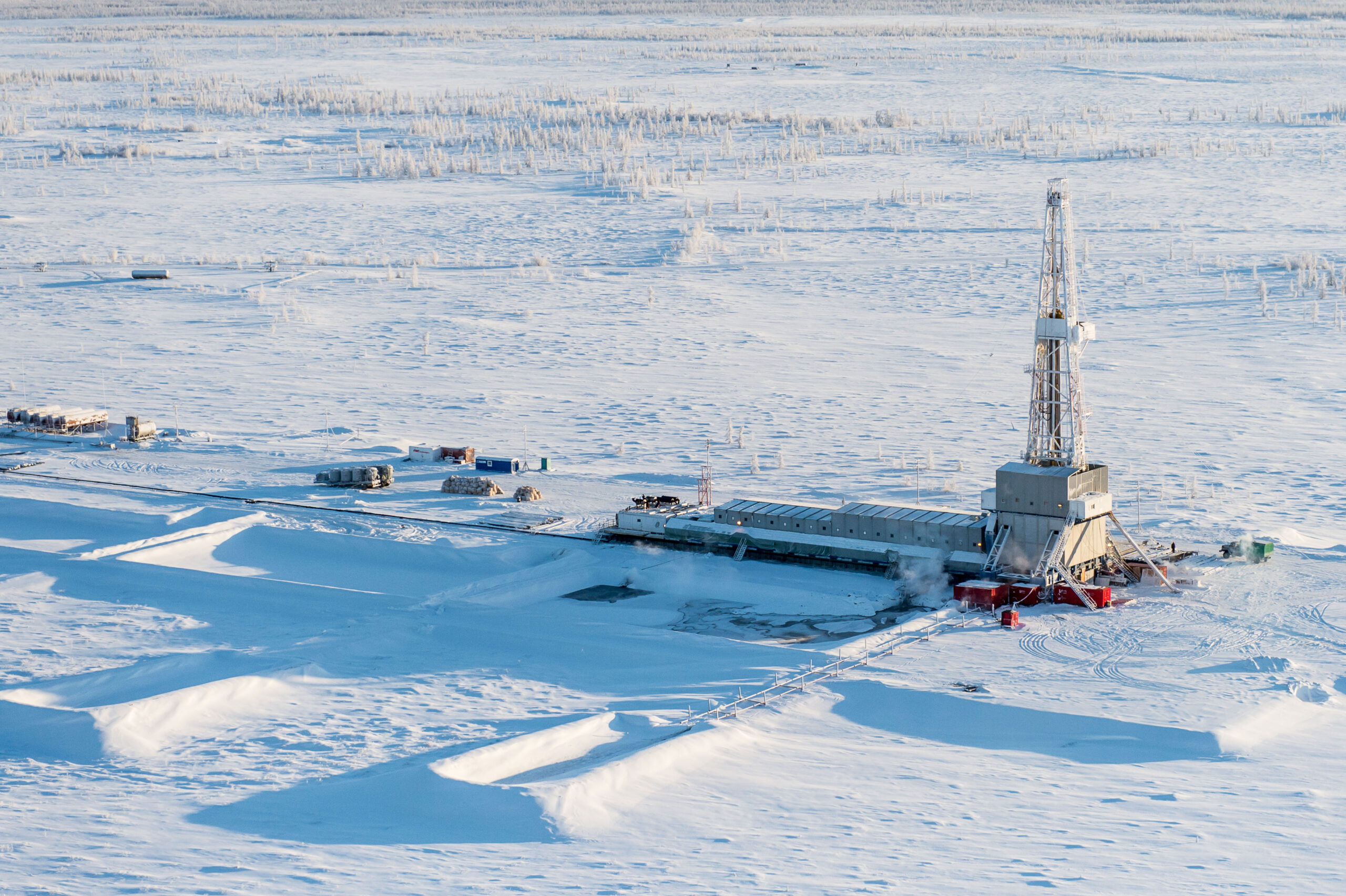

Shortly after signing a Green Alliance agreement with the EU, Norway offered more blocks in the Arctic for oil and gas exploration. Environmental campaigners are now hoping the EU will prevent an expansion of drilling areas, particularly in the Barents Sea.

In late April, the EU and Norway established a Green Alliance with the aim of strengthening joint climate action, environmental protection efforts and cooperation on clean energy and industrial transition. The agreement was signed in Brussels by the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, and Norway’s Prime Minister, Jonas Gahr Støre.

This is only the second agreement of its kind, following the EU-Japan Green Alliance signed in 2021. Although a small emitter of CO2 in absolute terms, about 0.11% of the world total, Norway’s position as a leading gas supplier to Europe – and also an oil producer – means its role in the energy transition should not be underestimated.

Skeptics will be quick to point out that the Green Alliance is not legally binding and that its content is open to interpretation. Yet that does not make it uninteresting reading. The pledges related to Arctic cooperation, for example, are noteworthy.

The agreement says: “Both sides intend to intensify wide-ranging Arctic cooperation and protect the region and inhabitants considering its environmental and geostrategic importance. In line with the commitment to keep global temperature rise within the 1.5 C-degree target they confirm that full respect for the precautionary principle in the region is paramount.”

According to WWF, this commitment means that there is no room for new oil and gas developments, let alone exploration activities, in the Barents Sea.

“Unfortunately, we observe that Norway, as it has done in the past, speaks out of both sides of its mouth in this matter. It presents itself internationally as a climate leader while at home urging oil and gas companies to ‘leave no stone unturned’ to find more gas in the Barents Sea,” the CEO of WWF-Norway, Karoline Andaur, told Gas Outlook.

She was referring to energy minister Terje Aasland’s recent comments about the need for more drilling and a gas pipeline to boost exports from the Barents Sea. This came as Gassco, the Norwegian state-owned pipeline operator, in a recent report, said building a new 5.5 bcm/year gas pipeline linking fields in the Barents Sea with existing infrastructure in the Norwegian Sea by 2030 would be economically profitable. Gas from the area can currently only be exported from the Hammerfest LNG plant.

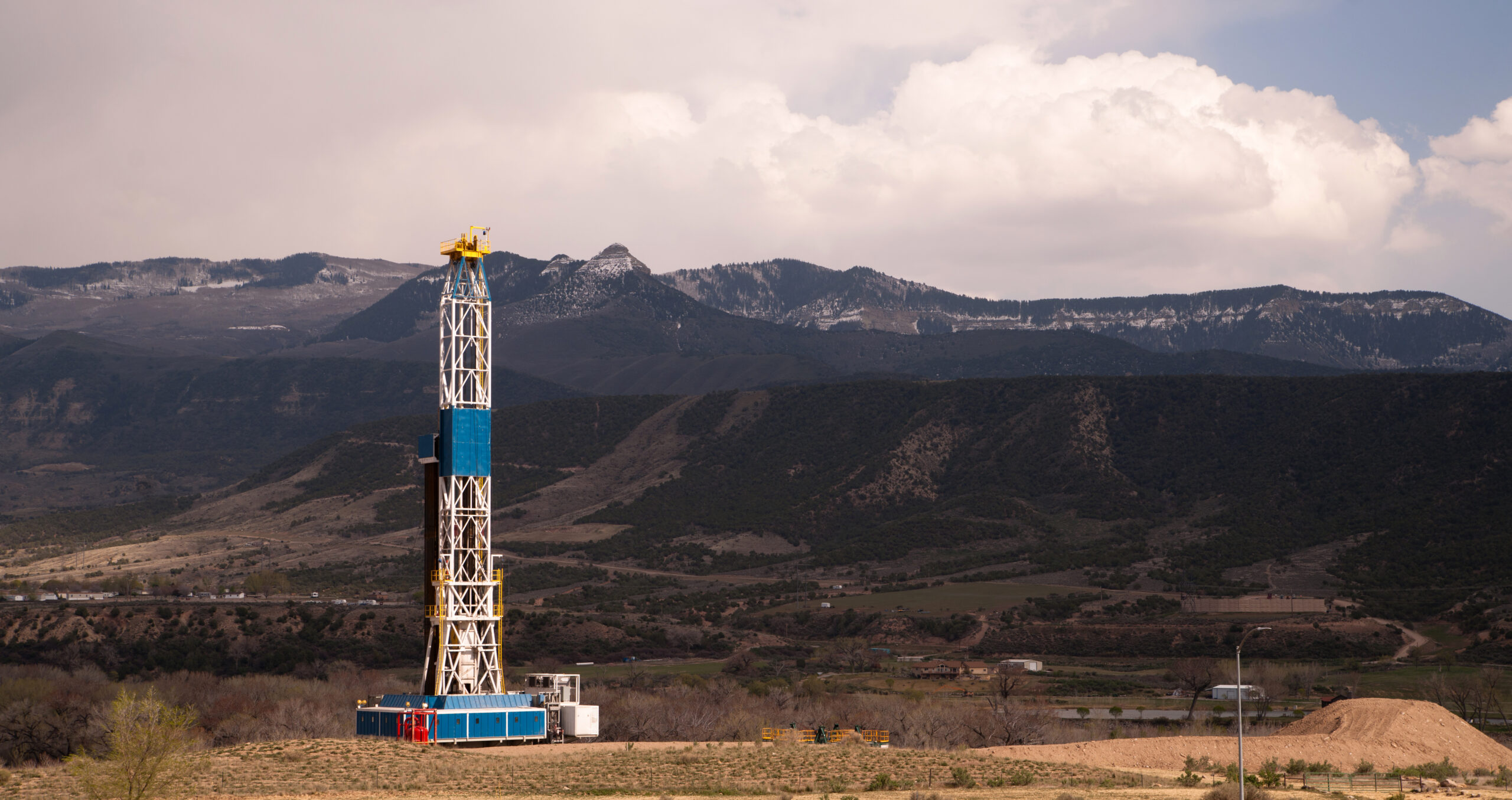

In a recent licensing round, Norway earmarked an additional 92 blocks for oil and gas exploration, mostly in the Barents Sea. However, environmental campaigners in Norway are now hoping the EU will exert its influence and prevent an expansion of drilling in Arctic areas.

”Norwegian authorities have used the EU’s energy crisis to justify an aggressive exploration policy in the Arctic, and the EU must refute this statement and emphasize its commitments from the EU’s Arctic policy of 2021, which pledges to keep Arctic oil, coal, and gas in the ground,” said Andaur. “This is why we place our expectations on the EU.”

Norway’s business daily Dagens Næringsliv has reported that during the negotiations of the Green Alliance deal, Norway tried to pressure EU countries in the midst of an energy crisis to support an increase in oil and gas exploration and extraction.

“The EU has stood up against the pressure and taken responsibility by getting Norway onboard for the precautionary principle and a more rapid transition away from fossil energy in the Arctic,”

Truls Gulowsen, leader of the Norwegian Society for the Conservation of Nature, told Gas Outlook.

“The [Green] Alliance explicitly says that the EU prioritises renewable energy, including green hydrogen, and not blue hydrogen produced from gas, the latter which supports the arguments for more oil exploration particularly in the Barents Sea,” he said.

Yet the most positive and concrete measure under the Green Alliance is that it obliges Norway to work together with the EU to reach the goals under the Paris agreement as part of an ambitious ‘climate club’ of different states, he said. This, together with the recommendations from the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, must lead to an end of Norway’s “aggressive exploration policy” in the North, Gulowsen stressed.

Norway has committed to reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by at least 55% compared with 1990 levels and by 90-95% by 2050. In the period 1990 to 2021, Norway’s total GHG emissions, in terms of million tonnes CO2 equivalents, decreased by 4.7%. However, emissions from oil and gas extraction increased by over 48% in the same period and now have a share of around 12% of total GHG emissions.

The energy transition in Norway is underway with a high penetration of electric vehicles, plans for 30 GW of offshore wind by 2040 and a number of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) projects at various stages of development. Moreover, the country’s power sector is relatively clean with over 90% of electricity produced by hydropower and the remainder mostly from onshore wind.

However, oil and gas production is the backbone of Norway’s economy and the transition away from fossil fuels will take time. The fact that Norway has replaced Russia as the largest supplier of piped gas to Europe – it exported about 122 bcm in 2022 – will do little to speed up the transition.